Enforcement

Effective non-tax tobacco control policies include advertising bans, plain packaging, and smoke-free public places.

The adoption of policies from the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) have contributed to the decrease in global smoking prevalence.

South Africa ranks 164 out of 206 countries that have implemented graphic health warning labels on cigarette packs, with a compliance score of only 21%.

This page discusses the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), considers the various types of non-tax tobacco control measures used by governments around the world, and presents estimates of their effectiveness in reducing tobacco use. It presents data on the exposure to tobacco advertisements and warnings in South Africa and discusses the impact of the Covid-19 tobacco sales ban. Cessation policies and approaches are discussed and lessons from the global tobacco control movement are presented.

To learn more about the data and methods used in this page, click here.

The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) is the first international treaty negotiated under the auspices of WHO. It was adopted by the World Health Assembly on 21 May 2003 and entered into force on 27 February 2005. It has since become one of the most rapidly and widely embraced treaties in United Nations history with 183 parties.. The Convention represents a milestone for the promotion of public health and provides new legal dimensions for international health cooperation. Over the last decade, the WHO FCTC has succeeded in keeping tobacco control high on the global agenda, while saving lives and improving global health. Measures outlined in the WHO FCTC emphasize the importance of using an approach that aims to minimize both tobacco demand and supply through a variety of measures. There is strong evidence that these measures effectively protect adults and children, equally, from smoking initiation, facilitate cessation and reduce tobacco-related harm. Read the WHO FCTC.

Key Aspects

Key Articles

of the FCTC

5.3 – Protect public health policies from tobacco industry interference

6 – Adopt price and tax measures to reduce the tobacco demand

8 – Protect people from exposure to tobacco smoke

9&10 – Regulate the contents and disclosures of tobacco products

11 – Regulate the packaging and labeling of tobacco products

12 – Education, communication, training and public awareness

13 – Ban tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship

14 – Offer people help to end their addictions to tobacco

15 – Control the illicit trade in tobacco products

16 – Ban sales to and by minors

17 – Provision of support for economically viable alternatives

18 – Protection on the environment

Map of Signatory Dates

to the WHO FCTC

- Period|

- less than 10 years

- 10 to 14 years

- 15 to 19 years

- 20 years or more

- No Data

Source: UN Treaty Treaty Collection

Click on the images below to read more about the impact each measure has had on smoking prevalence in various countries around the world.

Packaging and Warnings

Ban on Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and Sponsorship

Tobacco-free Public Places

Enforcement of Graphic

Health Warnings

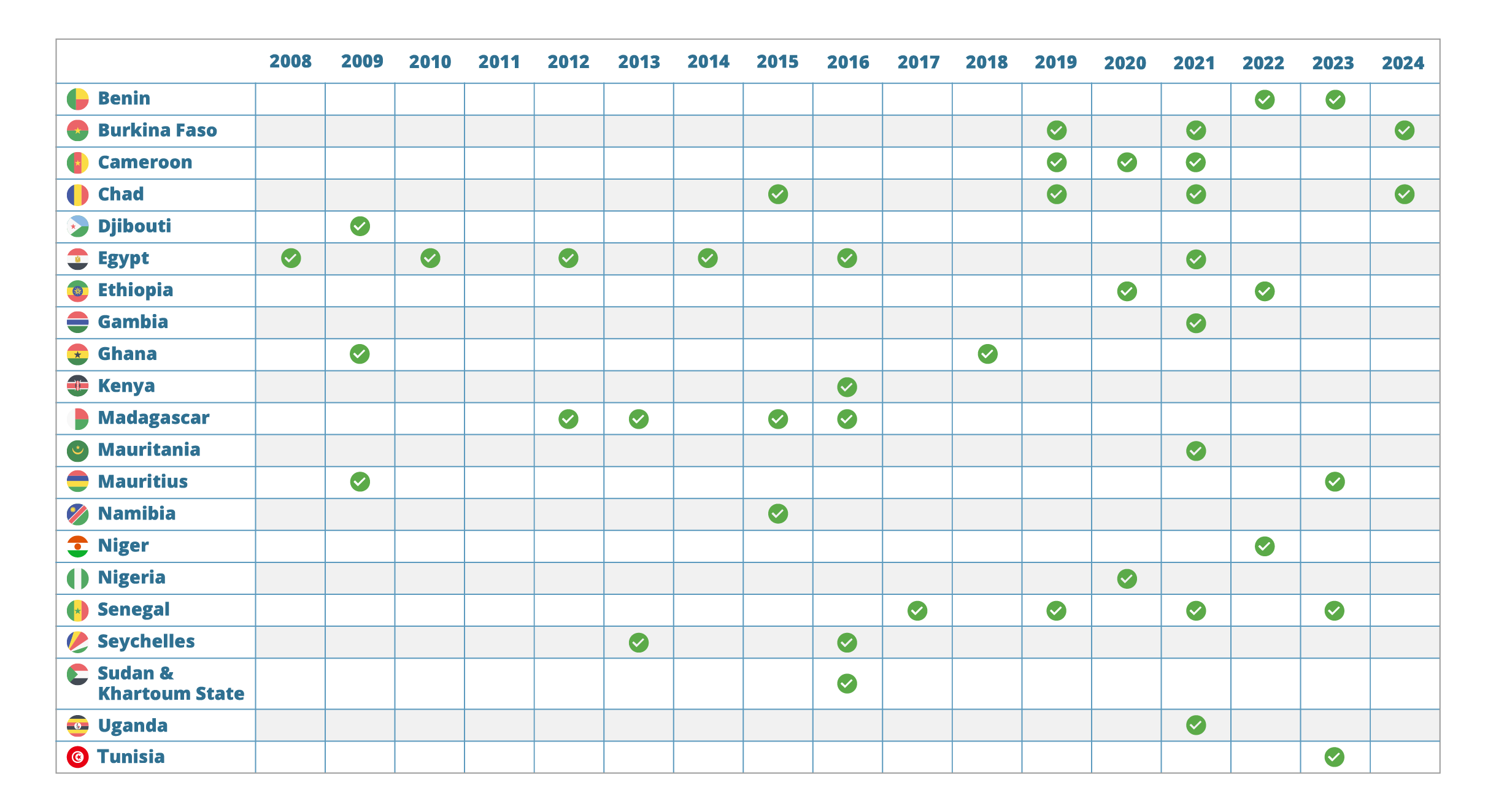

South Africa lags behind most African countries in terms of the implementation of graphic health warnings (GHWs) on tobacco products. Currently, South Africa has eight rotating text-only health warnings on tobacco packages which have not been changed since 1995. Urgent changes are needed to meet the guidelines of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control.

African countries that have implemented graphic health warnings

• NOTE: South Africa has not implemented graphic health warnings (GHWs) and lags behind most African countries in terms of implementation.

Source : Canadian Cancer Society, 2023

• About one third (30.5%) of South African adults have noticed anti-tobacco information on the television or radio.

• Among current smokers, intentions to quit smoking due to warning labels were higher among men (37%) than women (30.7%).

• Among smokeless tobacco users, intentions to quit were higher among women (27.1%) than men (16.5%).

Quitting intentions and anti-tobacco warnings among adult tobacco users, South Africa

Source: Global Adult Tobacco Survey, 2021

In 2020, as part of South Africa’s COVID-19 lockdown, the South African government imposed a ban on the sale of all tobacco products. While the ban was initially intended to last for three weeks, it was ultimately in place for 20 weeks (from March to August). South Africa was one of only three countries to ban the sale of tobacco during the pandemic, and its ban was the longest: Botswana banned tobacco sales for 12 weeks and India for six weeks.

While not necessarily nationally representative, various studies assessed the impact of the sales ban:Illicit Trade of Cigarettes

Illicit Trade of Cigarettes

• Despite the ban on sales, 93% of continuing smokers (aged 18 and over) purchased cigarettes during the ban.

• Both multinational cigarette brands and local/regional brands were sold during the ban. Smokers shifted away from the previously dominant multinational brands, such as Peter Stuyvesant, and rather favoured local brands, which were cheaper and more readily available.

• For many smokers, the ban may have normalised cheaper brands, which were more likely to be illicit, thus making smoking more affordable and accessible. This may have contributed to the increase in prevalence and illicit trade, observed in recent studies.

Cigarette Prices

Cigarette Prices

• The average price of cigarettes increased by 240% in June 2020, compared to before the ban.

• In the month after the ban, cigarette prices dropped back to slightly above pre-ban levels (3.6% higher). Many smokers continued to buy the cheaper local brands to which they became accustomed during the ban, despite the availability of multinational cigarettes.

E-Cigarettes Industry Tactics

E-Cigarettes Industry Tactics

• The e-cigarette industry used a variety of tactics to evade the restrictions on the sale of “tobacco, tobacco products, e-cigarettes and related products”. These included promoting CBD as a substitute product, allowing the sale of restricted items if purchased with CBD, and deeming ingredients for e-liquid and other e-cigarette paraphernalia as “essential items”.

Government Revenue

Government Revenue

• The National Treasury collected R7.5 billion from excise taxes from cigarettes in the 2020/2021 financial year.

• This is R6.9 billion less than what they had budgeted for that year.

• They therefore collected 48% less excise revenue than planned.

Smoking cessation can be encouraged with many different measures. Effective methods include nicotine replacement therapy, Champix, Zyban, training, counselling, quit-and-win schemes, and cognitive behavioural therapy.

Combining measures improves their efficacy. Quit rates quadruple when behavioural therapy is combined with nicotine replacement therapy.In 2010, signatories of the WHO FCTC

(which South Africa signed in 2003) adopted guidelines which encourage parties to implement tobacco cessation promotion activities, such as healthcare professionals screening for tobacco use, providing advice, and offering cessation treatments at clinics (all of which are shown to significantly increase the likelihood of smoking cessation).Although South Africa has made efforts to incorporate tobacco dependence treatment into the healthcare system, there was no evidence of an increase in the proportion of smokers receiving cessation advice between 2007 and 2017.

There was, however, an association between receiving cessation advice and making a quit attempt in all survey years, which highlights the importance of scaling up cessation advice in South Africa.Evidence-based nicotine-dependence treatment is not included in South Africa’s Essential Drug list and must be paid out-of-pocket, a challenge for many South Africans.

Including these treatments on the South African Essential Drugs list and adding coverage for smoking cessation treatment within the incoming National Health Insurance may increase access and utilisation of evidence-based cessation aids among smokers in South Africa.E-cigarettes have been promoted as a smoking cessation device, however, research is inconclusive on the effectiveness of e-cigarettes compared with nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or non-NRT medication.

Read more on e-cigarettes and smoking cessation.Considerations when designing

cessation programs

• Combination nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), e-cigarettes, varenicline, and cytisine are effective cessation options.

• Bupropion may be as successful as single‐form NRT in helping people to quit smoking, but less effective than combination NRT.

• Consider both environmental and individual factors when developing smoking cessation programs for young persons.

• Digital and online cessation services appeal more to younger smokers, women, and smokers with greater nicotine dependence.

For information on quitting smoking in South Africa, visit Go Smoke Free.

Cessation Behaviour

in South Africa

Among South African adults:

• 65.7% of current smokers planned to quit or were thinking about quitting smoking (Men = 66.5%; Women = 63.2%).

• 40.5% made a quit attempt in the past 12 months (Men = 40.7%; Women = 39.7%).

• 42.9% of smokers who visited a healthcare provider in the past 12 months were advised to quit smoking (Men = 42.5%; Women = 43.8%).

Quitting behaviour among adult tobacco users in 2021, South Africa

Source: Global Adult Tobacco Survey, 2021

Increasing numbers of countries are implementing tobacco control policies, ranging from graphic warnings and advertising bans to increases in excise taxes and the introduction of smoke-free laws.

Policies and programs designed to reduce the demand for tobacco are cost-effective. These include significant tobacco tax and price increases (see Taxation page), comprehensive bans on tobacco marketing, graphic health warnings, smoke-free public places, and the provision of wide-scale tobacco cessation programs. Of these interventions, significant tobacco taxes and price increases are the most cost-effective.

Control of the illicit trade in tobacco is a key supply-side policy to reduce the prevalence of smoking and its health and economic consequences. Other supply-side interventions, like restrictions on production, are generally not perceived as particularly successful or impactful. However, where there is a decrease in tobacco production, farmers should be helped to find other livelihoods.

The tobacco industry uses a wide range of tactics to oppose any policies that might reduce sales. These include strategies such as political lobbying, financing research, attempting to influence regulation and policy, and using corporate social responsibility initiatives as part of their public relations campaigns.